Art In Fiction

Find out what makes great, arts-inspired fiction in a variety of genres, from mysteries to crime novels, historical fiction, thrillers, contemporary fiction, and more. Art In Fiction founder and author Carol M. Cram chats with some of the top novelists featured on Art In Fiction, a curated online database of books inspired by the arts. Discover your next great read and get valuable advice on what it takes to be a successful writer.

Art In Fiction

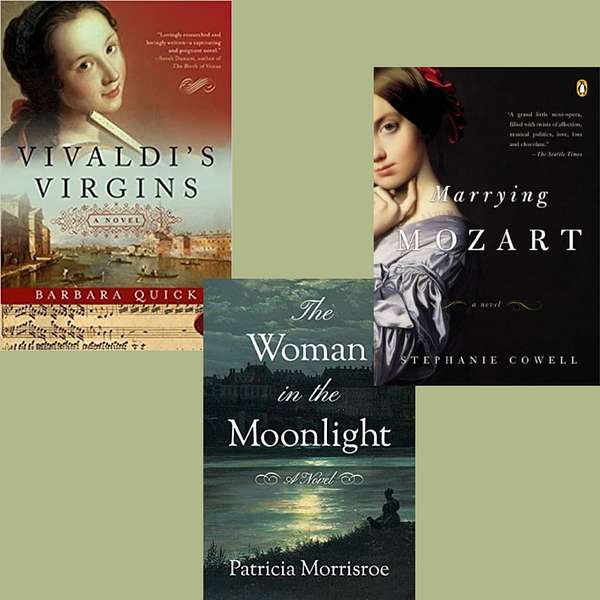

Vivaldi and Mozart and Beethoven, Oh My! Three Novelists Talk About Music in Fiction

Welcome to The Art In Fiction Podcast.

The three novelists you'll meet in this episode are each inspired by a different classical composer. They discuss their inspiration and research processes, and touch on a topic rarely discussed in author circles-: money!

Barbara Quick is the author of Vivaldi’s Virgins, Stephanie Cowell is the author of Marrying Mozart, and Patricia Morrisroe is the author of The Woman in the Moonlight about Beethoven's inspiration for his Moonlight Sonata.

Highlights:

- Barbara Quick: inspiration to write Vivaldi's Virgins after discovering that the 18th-century composer had been the resident priest and composer in an all-girls foundling home in Venice. She also discusses the integral role that Venice plays in the novel.

- Stephanie Cowell: inspiration for Marrying Mozart, a novel about Mozart's relationship with the four Weber sisters, one of whom he married.

- Patricia Morrisroe: how she came to write her debut novel, The Woman in the Moonlight, after a career in journalism

- Barbara: how she learned Italian to help her research Vivaldi's Virgins and the help she received from Vivaldi experts

- A reading from Vivaldi's Virgins

- Stephanie: the challenges of choosing which stories to include in the novel and what to leave out

- A reading from Marrying Mozart

- Patricia: the importance of fact-checking and extensive research

- A reading from The Woman in the Moonlight

- Writing and money (or its lack!).

Press Play right now and be sure to check out Vivaldi's Virgins, Marrying Mozart and The Woman in the Moonlight listed in the Music category on Art In Fiction.

Barbara Quick's website: https://www.barbaraquick.com/

Stephanie Cowell's website: http://www.stephaniecowell.com/

Patricia Morrisroe's website:

Are you enjoying The Art In Fiction Podcast? Consider giving us a small donation so we can continue bringing you interviews with your favorite arts-inspired novelists. Click this link to donate: https://ko-fi.com/artinfiction.

Also, check out Art In Fiction at https://www.artinfiction.com and explore 2300+ novels inspired by the arts in 11 categories: Architecture, Dance, Decorative Arts, Film, Literature, Music, Textile Arts, Theater, Visual Arts, & Other.

Want to learn more about Carol Cram, the host of The Art In Fiction Podcast? She's the author of several award-winning novels, including The Towers of Tuscany, A Woman of Note, The Muse of Fire, and The Choir. Find out more on her website.

Carol Cram:

Hello and welcome. I’m Carol Cram, host of the Art In Fiction podcast. This episode is called Vivaldi and Mozart and Beethoven, Oh My! and features my conversation with three music-inspired novelists: Barbara Quick, author of Vivaldi’s Virgins, Stephanie Cowell, author of Marrying Mozart, and Patricia Morrisroe, author of The Woman in the Moonlight.

Barbara Quick is the author of several books, including Vivaldi’s Virgins which has been translated into over a dozen languages. She makes her home on a small farm and vineyard in Northern California. Stephanie Cowell has written several arts-inspired novels listed on Art In Fiction, including The Players, Claude & Camille, and Nicholas Cooke: Actor, Soldier, Physician, Priest. Stephanie lives in New York City. Patricia Morrisroe is the author of three non-fiction books and was a contributing editor at New York magazine along with publications such as Vanity Fair, The New York Times, and Travel + Leisure. She also lives in New York City.

Carol Cram:

Welcome to the Art In Fiction Podcast, everyone. I'm so excited to have three authors to chat with today, all lovers of classical music, as am I. All three of your novels really resonated with me. Music has long played a huge role in my life. I play Mozart and Beethoven almost every day, badly, but I do it. And my second novel is about a woman composer in the 1820s and '30s and it actually opens in Vienna with the funeral of Beethoven in 1827.

So we're pretty much all on the same wavelength. Obviously, we all love classical music and all three of your novels are written mostly from the point of view of women who are in the lives of three great composers.

We'll talk about the novels in chronological order by composer, which means that, Barbara, I'll start with you. Your novel Vivaldi's Virgins takes place in Venice in the early 18th century at the Ospedale della Pietà—and I'm sure you can pronounce that better than I can—the foundling home where Antonio Vivaldi was resident priest and composer. Tell us about why you chose to write this story.

Barbara Quick:

Hi, Carol, good morning. I'm really glad to be with all of you virtually today. Vivaldi! Well, it all started with my hearing just a historical rumor that one of the Italian composers was also the resident priest and composer in an all-girls foundling home in Venice in the 18th century.

And that struck me as such an intriguing location. I guess, in historical fiction, as in real estate, it is sometimes largely a matter of location, location, location. I couldn't believe that someone hadn't already written a novel set in this place if such a place had existed. And I began digging in the library and trying to figure it out and found that it was indeed Antonio Vivaldi, who was known as il prete rosso, the red priest of Venice, for his flaming red hair.

And he was the resident priest in this foundling home called Ospedale della Pietà and he taught all these women and girls who were cloistered there. They weren't religious nuns, they were, but they were cloistered and they were supported by the state. And he was the only man who ever saw their faces.

So it struck me as so intriguing. I also, like everyone else, I had grown up hearing Vivaldi's Four Seasons, hearing his music and loving it, and I wanted to learn more. So it became a treasure hunt to learn more about Vivaldi at this time, the historical person and about the girls and women, the real people, who were his students and who were shut up there in that cloister in Venice, which is truly the most magical of all cities in the world.

Carol Cram:

It certainly is, oh, I love Venice. And that was a thing I loved about your novel was how it took me back to Venice. And also how it still feels like Venice today. Venice today still feels like it's the 18th century, even with all the tourists and everything, but at night it's so magical, isn't it?

And you really brought that to life.

Barbara Quick:

Thank you. No, I had that feeling there while I was doing my research. I made four separate research trips to Venice and spent a lot of time there really just immersing myself in the atmosphere and, and the sensual surroundings there, then, much of which is still the same. And all you have to do is sort of mentally edit out the electricity and you're there again. Of course, there are no cars in Venice, even now, which is quite wonderful. There are still all the gondolas.

There's still the sense of being surrounded by water, and water becomes such an important part of the landscape for these girls and women who couldn't travel beyond the stone walls of their cloister, except by gazing out the windows at all the traffic going by in gondolas on the lagoon below them.

It was very evocative and it was very, weirdly easy to conjure up these lives and to find out real things about these people that had never been explored before in fiction. What amazed me is that within five years of the publication of my novel, in one case 10 months after, five other novels came out that had the same setting, but I got there first.

Carol Cram:

I noticed that. Interesting, you started a trend.

Barbara Quick:

I think that creative ideas sort of float around the world. And, you know, this one happened to reach me first. I'm a pretty good antenna.

Carol Cram:

Thank you, Barbara, for giving us a quick overview of Vivaldi's Virgins and especially the role that Venice plays. I also just loved the relationships between those girls and the women and just how clinging and cloistered it was. And yet they were sort of united with their love of music. That must've been a lot of fun.

Barbara Quick:

Oh, it's absolutely wonderful. I mean the only instrument I play is a fountain pen, but I did immerse myself in the world of Vivaldi's music and the music of the time. And I spoke to many, many professional musicians. And it's really funny because after the paperback came out several years after the novel was first published, I ended up marrying a string player from the San Francisco Symphony. So after having been imaginatively immersed in the world of string players, I am now truly immersed in the world of string players.

Carol Cram:

Oh, lucky you to be able to hear that in your house. I'm married to a drummer. So, you know, it's not quite as… He's a painter now, but I met him when he was a jazz drummer.

Stephanie Cowell, your novel Marrying Mozart revolves around the four Weber sisters, one of whom Mozart eventually married, Constanza. So I understand why you'd want to write a novel about Mozart, but why through the lens of the Weber sisters?

Stephanie Cowell:

As you probably know, I spent many years as an opera singer and I had first seen my first Mozart opera at the Met when I was 12 or 13. And it was the Marriage of Figaro. I never left the whole time. I was so afraid of missing one single note. I'd never heard anything like that in my life. It was great.

So now, how did I, how did I do this particular novel? Well, I was a singer for quite a while and for various reasons I switched and began to write and I had published three novels and I was in the middle of doing another one and it was all very, very heavy and very, you know, tragic in certain ways. And I, I had certain events in my life in which I really needed to do something lighter.

And so one day I took myself off to this wonderful place called the Café Mozart, and I ordered myself a Viennese cookie, and something fattening and delicious and serving them, they were playing one of the Mozart horn concerti on the sound system, which was just, absolutely, I can't remember which one, but it was just marvelous.

And I suddenly said, well, well, you know, I'd read a lot about Mozart, you know, here and there. And read his letters and went to Salzburg and things like that and so I knew that he had, he had met a family of four musical sisters when he was 21 and couldn't make a living and just grown up and dying to get a hold of any woman who'd sort of have him and here he was. There were four of them there.

So I wrote on the napkin, which is what I had, uh, just jotted ideas and I, I took it back and, you know something, I don't, it's funny. With a lot of my novels, I can sort of remember writing them, but I can't really remember this. It was a very hectic period in my life. My husband was quite ill for a number of months and I was working at a regular job to make money. And I really do not remember how this came together, just listening to an awful lot of Mozart.

And I just, they just came alive to me, the, these four quirky sisters and their mom who wants them to marry somebody wealthy, not some poor composer. And his dad, Mozart's dad, doesn't want him to marry anything and poor Mozart who just wants love and music.

I wanted happiness and joy, and I found it the operas and then it just sort of flowed onto the page. Uh, I don't know how, but it got there.

Carol Cram:

And it's wonderful. I actually just finished yours the other day. And it was so much fun. I love the mother and, and yeah, it's as you said, the personalities of all four of the sisters are so distinct and all the family dynamics that you get in there. So just as, you know, as a novel about a family, it's fascinating, but then of course you weave in Mozart and the music, and you have quite a few scenes from Mozart's point of view, which must be a little bit challenging to write, because how do we really know?

How did you get into Mozart's head?

Stephanie Cowell:

It was a big leap.

Carol Cram:

What a head to get into!

Stephanie Cowell:

Well, I, I read a lot of his letters and that wonderful, wonderful tone he had, and his combination of being deadly serious and terribly musical and also just a young man who wanted love and made fun of things. It was, could be very silly.

And I had to go, go lightly on, on the musical side of him because some people would relate to the, the really musical side when he was composing and some people wanted the relationships. So it was a combination, but it was just lovely. I don't know. I mean, his music just led me into it, as I said, it flowed onto the page. I wish I had an early draft somewhere. I don't remember putting this thing together. I just remember it being formed. It was very strange for me. It was nine months, and nine months, very fast.

Carol Cram:

That is very fast.

Stephanie Cowell:

My then agent who was expecting my big, tragic fourth century novel looks at this little Marrying Mozart and said 'what on earth is this? I can never sell this.' So I cried and cried and cried. I really, you know, called up my husband sobbing and things like that. And several friends of mine who read it and one sent, sent it to her agent who took it immediately and sold it immediately.

So I guess I could say what one agent likes, another agent will not like, and what one agent does not like, another agent will say, oh my goodness, this is for me.

Carol Cram:

It was just like readers, isn't that amazing? Actually, just hearing you talk about how it flowed from you, it kind of reminds me of how Mozart himself composed, right? Because he actually wrote fair copies right from his head, didn't he?

Stephanie Cowell:

Yeah, he did. He did. He wrote fair copies and but he, um, I think he had it in his head.

Carol Cram:

Yes.

Stephanie Cowell:

And if this was in my head, I had no knowledge of it. I just had no idea what was coming out through my fingers. I think it really was all those years of just totally loving, adoring Mozart, I mean, I went to Salzburg and I cried over his, you know, this display cases with his buttons on, in them and everything like that and lock of hair and stuff.

And it was a tremendous love relationship that I think was going on, kind of a love affair for a long, long time in my life before it suddenly, thanks to that horn concerto and that Viennese coffee, suddenly started to become what it is.

Carol Cram:

Oh, that's wonderful. And of course, yeah, Mozart is just such a compelling figure. Well, thank you, Stephanie.

Hello, Patricia.

Patricia Morrisroe:

Hi.

Carol Cram:

Lovely to have you on today. So your novel, which I believe is your debut novel, The Woman in the Moonlight, is about the woman who Beethoven dedicated the Moonlight Sonata to, and I gotta say, I really love your description of your own relationship with the Moonlight Sonata that I saw on your website.

You say that in 16 minutes, you went from sorrow to happiness to defiance. And I thought, what a great summary of how Beethoven's music affects me and I'm sure many, many other people.

So tell us why you chose to write this story about the Countess Julietta.

Patricia Morrisroe:

I really fell into it. Um, I, wasn't sitting around saying, oh, I'd like to write a historical novel about Beethoven. It really happened over lunch, actually, five years ago this month with a colleague from my magazine days who was an editor and he just threw out an idea and he said Beethoven had been in love with one of his young piano students and he thought it would make an interesting novel.

I had a book come out maybe six months prior to that. I had been in between doing some travel writing. So I had traveled a lot and perhaps was incredibly jet lagged and exhausted when I said, oh yeah, I think I can travel back in time and did that.

But I started to research and there was very little written about her, which is a plus and, uh, a minus. If there had been more written about her, I was thinking of doing it as a biography, because as someone who's written a biography and as someone whose life had been spent in non-fiction, I knew that that would probably be more comfortable for me.

But there was virtually very little about her, but I, I began the research and it's very odd that the things that stick in your head. One of her cousins was Josephine von Brunsvik, who, um, is one of the leading candidates to be Beethoven's Immortal Beloved. And she wound up being married off to a man who was the proprietor of Vienna's top tourist attraction, a cabinet of curiosities and a wax museum.

And it was below her 88-room palace where she lived with this husband that was 35 years older and it was an arranged marriage. The idea of these wax figures and the idea of these strange contraptions he had in this cabinet of curiosities just drew me in.

And from there, of course I found Beethoven, but that to me was such a visual image. I couldn't get it out of my head.

Carol Cram:

You just never know what's going to pull you into writing about something. Yes, and I, I presume of course you went to Vienna.

Patricia Morrisroe:

Yes I've been to Vienna before, and I did go. I also went to Prague because I wanted to be able to get a feel for what old Vienna looked like because Prague had been untouched by the War. You know, walking around Vienna and seeing the remaining places where Beethoven lived—well, he lived in so many different places, 68 different places—it didn't impact me as much as actually doing the research in my office, reading the letters which I found enormously helpful, reading, really everything I could get my hands on while listening.

I listened to a lot of course of Beethoven's music. And even though I did grow up in a musical family, my grandfather was a music teacher. Um, my sisters, we all played piano. I sang. So that aspect of it was comfortable for me, but it never dawned on me that really, and it's so obvious, that writing music is a different type of storytelling and listening to Beethoven very closely, you just realized he was telling his own story.

And that helped me, the concept of the Moonlight Sonata that he wrote when he was grappling with a realization that he would probably eventually lose his hearing and as Vienna's top piano virtuoso, this was going to completely end his career. So you see that unfold in the Moonlight Sonata, how the first movement is really a funeral march and like Beethoven as he always does, he greets everything with a measure of defiance. And that third movement is quite defiant in a maniacal way.

But he met Julie during this time, Julie, the woman he dedicated the Moonlight to, Countess Julie Guicciardi. And that was just at a very critical time in his life. And, you know, he called her his dear, enchanting girl. Uh, and in a letter to her friend, he wrote she loves me. I love her. It's the first time I think about getting married, but she's not of my station.

Carol Cram:

Yes. That was really interesting how you wove Julie's story and all the various things that happened to her, then touching in with Beethoven every so often through the course of the novel. I love how you showed Beethoven's increasing despair, knowing that, of course he was going deaf. I can't even imagine.

Patricia Morrisroe:

I mean, Beethoven had so many physical ailments. And it was really not to be believed, you know, he had so many stomach problems. And I think it's interesting because in reading the letters, Beethoven would complain much more about his stomach than he really did about his hearing because I think once it dawned on him, all right, that's going to be the end of my performing career, he was very confident that he would be able to keep composing.

He heard very well until he was 30. And even at 30, it was diminished hearing. It was buzzing. He had difficulty hearing the high registers of notes, but I mean, he could still hear somewhat about two years before his death. People thought that he was completely deaf during the Ninth Symphony, but new evidence is coming out that that wasn't the case.

Carol Cram:

Oh, I didn't know that. That's interesting. Now each of you have touched a little bit on your research methods, but I'll ask you to say a little bit more about some of the challenges that you encountered doing the research because of course this is historical fiction. And then if each person could do a short reading.

Barbara, we'll start with you.

Barbara Quick:

Well, when I first conceived of the idea I had actually already just started learning Italian. So that turned out to be very handy because all of the archival material at the Ospedale della Pietà is in Italian, it's in handwritten Italian.

So, you know, it really required a reading knowledge of Italian. And there were various really wonderful people I was able to contact and in Venice and who helped me. One of them is the head of the Vivaldi Institute in Venice, but he didn't speak English. And, you know, my Italian has never been totally fluent. So, you know, but he was very patient with me and we stumbled through together and really, I just developed a tremendous sense of gratitude to him.

Also, there was a British researcher who was living and working in Venice, she's been there for decades, named Mickey White, who has made a study of Anna Maria del Violin who's actually the main character in my novel, or she's, I guess she's working on a study. It hasn't happened yet, but she's been poring through the archives of the Ospedale and they're not translated, but she was a font of information. She's a little bit suspicious of novelists so I had to really backpedal a few times when I was talking to her, but she literally let me in, into the, what remains of the buildings so that I could stand there where the girls drew their water from the well and outside the windows where the governors met to make their decisions that affected the lives and futures of these girls and women.

And the water gate where the gondolas would pull in. So she unlocked a lot of doors for me, but mostly it was just a matter of reading and reading and reading and reading. And when I first started the research in, in 2004, you know, there, there wasn't as much available on the internet as there is now. So I did a lot of work in libraries and in Venice and also at research libraries in the United States.

Carol Cram:

Oh fantastic. I love how you're talking about your relationship with experts, like, consulting with experts and how helpful they were. Because I've found that too, over and over that, uh, academics in particular, I've found have been very helpful. Although you said that one was a bit reluctant.

Barbara Quick:

Yeah. She, she's actually a nonacademic. She's a, you know, sort of an amateur, but she was very proprietary about the subject matter, you know, just as I became, so I can understand it. It's like you're sifting through the ashes of the past and you find this absolute gem and the impulse is to, to feel that it's your discovery, it's yours. No one else should do anything with it, but you just want to contemplate it until you see every single detail that can be found.

And that's what happened with me when Anna Maria became my main character. I didn't start out that way. I didn't even know about her. I had made up a fictional version of Vivaldi's favorite violin student. But then when I found this real person in the archives who actually matched everything I wanted for this person, she just called out to me.

And, you know, sometimes I would just it's, it's like what Stephanie said, that, that the novel just seemed to pour in through my hands to my notebook from the ether somewhere. This person really wanted her voice heard. That's how it felt.

Carol Cram:

She was such a great character. I just, I loved her. I really cared about her. And the way that you wrote it in two time periods, you know, when she was young and when she was older, it was, it was a great character study as, as well as being about the times and the setting and Vivaldi.

Would you do us the short reading?

Barbara Quick:

I would love to. This takes place towards the end of the novel. And I've chosen to read this because I'm in the midst of the fires in California now. And I don't know, maybe it's made me a bit morbid, but I do love the scene. And I'd like to share it. It's when Anna Maria is in a gondola with this other character Silvio.

The Lido hove into view—an unprepossessing shoreline of sand and scrubby trees, and so long that it was hard to think of it as an island at all. Silvio gave the gondolier a handful of coins, telling him that we would be a while.

We walked for a long time through sand dunes, and then along a wooded pathway, and finally through a gate. The white Istrian stone of the monuments was even whiter for the moonlight washing over them. The headstones leaned every which way, as if the dead were gossiping with those they loved in life and pulling away from those they loathed. Some pairs of headstones leaned against each other, melted together, in death, into one.

The older stones were grown over with trees and vines and half-covered with brambles. Walking among them, I felt the spirits of the past hovering round me.

Time has a very poor memory. We each of us do what we can to be remembered—but most of us are forgotten.

If someone had asked me, that night on the Lido, who, among all those I’ve ever met, I thought would live on in some way, I would have been hard pressed to name more than half a dozen. Vivaldi, surely. My uncle Marco Foscarini, if he lives long enough to become Doge. Gasparini and Handel. Scarlatti and, the only female among them, Rosalba. The various popes and royal personages—Time always saves a place for these in her guest-book.

But what of all the rest of us? I knew that each one of those blocks of stone in the graveyard stood for a life that was lived. Within each grave beneath them reposed and rotted the mortal remains of someone, like myself, who yearned, who wept, and laughed and loved. Not one of them ever believed that what they strived so hard to achieve or avoid—the person they held most dear, their fondest dream, the secret they kept, the one thing that inspired their devotion: all of it would be as forgotten as surely as yesterday’s rain.

The legends on the tombstones are eventually worn away as the stone is eroded by rain and wind and centuries. Better to slip away quietly after having lived as fully as one can, doing the very best one can with the gifts one has been given. What more can a mere musician possibly hope for?

Music cannot be kept or captured. It unfurls in one miraculous moment in time and then it’s gone. The glorious sound of Marietta’s voice in a cantabile aria will be forever lost after she is dead and all of us who ever heard her are dead, too. No matter how well I manage to play, my playing will be forgotten when all those who have heard me have died.

As Silvio and I walked through the Hebrew cemetery of San Nicoló di Lido, the sand worked its way into my shoes, so that I knew I would carry a small part of these graves back with me to the cloister. It is tonic to be reminded, once in a while, that we are but specks in the world and as easily swept away.

Carol Cram:

Oh, that was wonderful Barbara, thank you so much. I was totally engaged in it.

ADVERTISEMENT

Time for a short break

I love using SmarterQueue to manage my social media accounts. It’s reasonably priced and very easy to use. I particularly appreciate the color-coding that helps me organize all my posts across several platforms! SmarterQueue saves me time by automating my social media activity.

Follow the link in the show notes to receive a free extended trial of SmarterQueue.

And now back to the show.

Carol Cram:

I'm going to go on now to Stephanie, and Stephanie, same question about research and some of the challenges.

Stephanie Cowell:

Okay. Well, my research process, I think I was able to get a great deal on Mozart. He's very, very documented. And the sisters, I had a difficult time finding out great deals about them, except the one he married and then shortly after I did the book, more information came out on them. Of course I had to make up a great deal about them.

Aloysia, who became a great singer, Josepha, who was the first queen of the night, Constanza, we won't say more about her. She also sang and Sophie, the youngest one.

I think one of the hardest things in research to me was I got so in love with the characters and, you know and I had written, basically written the book and really couldn't cram anything else into it. And then I'd find out that Mozart had gone to coffee at this certain house at four o'clock on a certain day, and I suddenly felt that was the most important piece of information. And I had to make room in the book for this coffee drinking with this noblewoman. And of course there was no room in the book.

So I'm always finding things as I continue my research mostly because I'm addicted to it. I love to find out what he was doing on Thursday morning, having this coffee. And then you realize of course that you can't put all these things in, because even though it was true, you wouldn't have a book, you'd have a book that they really didn't move. Too much coffee.

Carol Cram:

It's quite a challenge, isn't it, about what to leave out with all your research.

Stephanie Cowell:

Yeah. Hard to leave out things that are quite quite wonderful. This goes for scenes as well. Just wonderful stuff. A novel is a story. It's not life. It's a story about a particular part of life. And you have to stick to that story. Otherwise, the reader won't quite know where you're going and they will say, they'll say, where on earth is this book going?

All my readers of this never knew exactly where he went for coffee on Thursday morning. I'm so sorry, but it was a sacrifice.

But anyways, so I'd like to read you, I have so many favorite scenes in this. They're so charming. But this one is probably about two thirds into the book. The young Mozart age 21 has been attracted in various ways to all four sisters, least of all the youngest, Sophie. She's very plain and loving and sister-like and everything like that. And he's on hard times and he's gone to live as a boarder with their mother who has opened a boarding house. She also has hard times and the other three older sisters are off doing whatever, starting a music career, falling in love elsewhere. And so the mother has this great idea for her plain, youngest daughter and tells her, I know exactly what you must do. You must go and marry Mozart.

Gently she rapped and whispered his name, but there was no response. Finally, she creaked open the door and as softly as possible tiptoed across the room and stood looking down at him. There was some light from the moon. She bent over him a little and as she did her spectacles tumbled from her nose and fell across his chest. He woke, blinking, rather astonished. He gazed up at her, his hand half in front of his eyes. He moved to site up and the spectacles slipped off the bed to the floor.

“What is it?” he said, not awake enough to speak clearly.

“I’ve lost my spectacles, that’s all,” she said. She dropped to her knees and felt around the side of the bed as well. “The problem with dropping my spectacles,” she said, “is that I can’t find them unless I’m wearing them.”

“Let me help you,” he said. He groggily rolled to his side and felt down the side of the bed. “I think I’ve got them,” he said. “What time is it? What are you doing here? Are you sleep walking? Is something wrong?”

She said, “I must . . . speak with you.”

“Very well then, but keep your voice low. It wouldn’t do for anyone to know you were here. They’d think the worse. You’re shivering; take my extra cover. Give me your hands; they’re so cold. What on earth are you doing here? What do you need to speak to me about now? What time is it?”

“Some past two.”

“It couldn’t wait until the morning?” he asked.

She shook her head.

“Then tell me, dear Sophie,” he said with his old affection.

She sat down in the chair, wrapped in the blanket. Pushing her glasses up, she sniffled a little. In the near darkness she could feel her face redden and now he looked at her in a kindly, steady way. He had large eyes. Sometimes they were suspicious, but now they were tender. She didn’t care if Aloysia said his nose was much too big for any woman to take him seriously. She found it a good, comforting face and he was strong enough, even though he was small for a man.

“My mother wants me to marry you,” she said simply. “She wants to make sure that no one seduces me, and that she’s taken care of in the future. I have always liked you. In fact, I love you with all my heart, but not that way. I want to renounce the world for God. I’m sure I’m not suitable for marriage. Still she says we must marry, and I don’t particularly want to. I want to know what you feel about it. We could go to Father Paul together and ask him.”

He said nothing for a time. Some anger passed his face, and she cringed a little, for she knew from some musicians who had lived with them that Mozart could be as touchy as gunpowder. Then he passed his hands over his lips and his shoulders shook and she could see he was laughing.

“It’s not so funny,” she cried, leaping up. “I’m not so bad that it’s funny.”

“Bad? No, not at all; you’re a darling. Oh my sweet Lord, do you really...”

“Hush, hush…Mozart,” she said. “Someone’s coming.”

They knew the drunken singing, the slipping, the muttering, the cursing. It was Steiner the theology student who was coming home drunk again. His room was opposite Mozart’s, but he did not go into it. He seemed to have stumbled on the stairs and sat there muttering and singing to himself, blocking any possible escape for her from the room.

Mozart put his finger to his lips. “Be very still, you darling,” he whispered. “Let me see if I can get him to bed, and then you can slip upstairs. We’ll meet in the daylight and talk about this.” At the thought he began laughing so hard he could hardly stand straight. He took a deep breath, walked across the room and through the doorway. His light brown hair stood almost perfectly upward from his sleep, giving him some several more inches in height. He looked ready to take flight. She sat down on the chair with her hands in her lap. She heard his voice from the hall in a stern whisper.

“Steiner...up now, man, to bed.”

“Can’t stand...stay here...stairs…” said Steiner.

“Come, Steiner, you can do it.”

It sounded like Mozart was trying to help the drunken student stand which would have had its difficulties, for Steiner was hundred pounds heavier and half a foot taller.

“Help me, Steiner,” she heard him say.

“Leave me alone...you bastard composer, you organ grinder...sleep here.”

And if you want to find out how Sophie gets from the room without Steiner seeing her, you will have to read the book.

Carol Cram:

You have to read the book. Yes, I remember that scene. It was great. Thank you so much, Stephanie. I'm going to go on now to Patricia.

Patricia Morrisroe:

Having spent so many years in journalism, it was very important to me that I get everything as accurate as possible. So I probably spent a good two years just researching before I put a word down on, I was going to say on paper, until I, uh, typed something into my computer.

For me, one of the challenges was obviously Beethoven, a titan and there was a lot written about Beethoven and I read almost all of it. But I was coming into this completely fresh. I really knew very little about Beethoven. I didn't know much about the period. I didn't know really that much about Vienna during that time. And then I had the added complication of my narrator, Julie Guicciardi, left Vienna, uh, to move to Naples with her husband, who's always referred to as the moderately talented Count Robert van Gallenberg.

So once I felt that I had finally grasped somewhat of what Vienna was like in the early 1800s, it was, oh, no, now I'm in Naples. And I had to really do research on what was going on in Naples. Her husband was a composer, ballet composer at the Theater San Carlo.

So it brought in a whole new cast of characters, a whole new location. And then I had to go back to Vienna and, I mean, I was getting out old maps of what Naples looked like then, you know, the menus in terms of what they were eating. It was very, very important to me that everything be as accurate as I could make it. And then, you know, of course, not only are you dealing with Beethoven, but Napoleon. And it was like, oh no, please, do we have to have the Napoleonic Wars, but we did so not that I wrote extensively about them. I didn't, but I had to know enough to be able to write about it at least somewhat intelligently and correctly.

There was a lot of moving parts and there were a lot of characters in this book. So it was very complicated and I was researching really right up until the end. I had almost finished the book, but I convinced my husband that we had to go to Naples because I have a scene where Julie is looking out her window on to Vesuvius. And then I thought, oh my God, maybe the windows don't overlook Vesuvius.

So when we were walking up and down and I, you know, saw that the house that I had picked out indeed looked over Vesuvius. So I was, I was fine after that, but I think it's always that fear, oh, you're going to make a mistake. Um, and I just didn't want to, uh, and I may have, but I haven't heard about it. I love to research. I really do. And that was, it was a lot of fun, but you know, it was very extensive.

Carol Cram:

Yes. Uh, that's interesting about going to the place too. And um, I know, I always love to go to the places that my novels are set. So it's a great excuse for traveling or at least it used to be. And, and you're right. If you get something wrong, someone will find out.

Patricia Morrisroe:

Yes.

Carol Cram :

And they'll tell you.

Patricia Morrisroe:

You certainly know that, uh, when you're writing journalism, because people are writing in immediately. Here, it's a little bit later, but yeah, you want it. With Julie, because people didn't know that much about her, I still tried to be accurate, but with Beethoven, you know, I couldn't put the Ninth Symphony in 1817. So that was challenging.

And then also describing the music. That was a real challenge to me because I wanted to describe it the way Julie would have heard it then, not the way I'm hearing it now. So if she's listening to the Grosse Fuge, for example, she's thinking, oh my God, what am I listening to? And indeed many people probably say the same thing when they listened to the Grosse Fuge, but it was really translating the way I heard the music into the way a 19th century woman would listen to Beethoven's music.

Carol Cram:

Yeah. What a, what a challenge that is, and it is difficult to write about music. I know I, I did that in my second novel and how to describe music. It's like, it's also a challenge when you're describing visual art. Yeah.

Thank you for that, Patricia. Now, would you like to do a short reading from the novel? That'd be great.

Patricia Morrisroe:

This is the beginning.

Vienna 1799.

His hands terrified me. They were strong and muscular, broad at the fingertips and flecked with coarse black hair. As he played a fantasia—an improvised piece that reflected his mood and imagination—he pummeled the keyboard with a bestial force that made the instrument tremble. Sliding a hand up and down two octaves, he delivered the equivalent of a double slap. My cheeks stung in sympathy. He scowled and grunted, the shadow of a beard eclipsing the lower part of his face. Was the great Ludwig van Beethoven turning into a werewolf? My mother and I had been waiting for my Hungarian relatives at the Golden Griffin, a modest inn not far from the Kärntnertor Theater.

Through charm and sheer persistence, Josephine and Therese had managed to persuade the greatest pianoforte virtuoso in Vienna to give them music lessons during their holiday. Aunt Anna had even rented a Walter pianoforte, which barely fit through the door, receiving numerous scrapes and an ugly abrasion that ran down its leg like a knife wound. I’d been living in Vienna for the past year but had never heard Beethoven perform. With my relatives’ tardiness and Beethoven’s unwillingness to converse, I had asked if he’d play a little something for us.

This, in retrospect, was a serious breach. People who asked him to play anything did so at their peril. Beneath a vaulted ceiling, with hunting trophies on the walls, he unleashed the musical equivalent of rage, teasing us with multiple climaxes and playing louder and faster until I feared my heart would burst. The pianoforte groaned and swayed; its maimed leg crackled. The innkeeper, covering his ears, fled the room.

I started to follow, but Beethoven, lifting his burly hands, paused for a few seconds. I knew what was coming next. He was going to kill us. But he suddenly played a melody that was so tender, so exquisitely sensitive that I couldn’t believe that it flowed from the same surly individual. I looked at his hands again. They had now assumed the graceful contours of a gentle lover caressing his innocent bride. I felt light-headed, imagining those hands around my waist, warm, still vibrating with passion.

Beethoven’s hands . . . the last thing I remembered.

Carol Cram:

Thank you. That was wonderful. I could totally be there and see that, and well done.

Well, that's great to hear everybody's readings and to just immerse ourselves in this wonderful historical fiction.

I'm going to finish off by asking each person just fairly quickly to give us one piece of advice that you'd like to share with new authors. Like, what piece of advice did you wish you'd known when you started on this journey of becoming a novelist?

Barbara Quick:

Oh, that was so wonderful. I'm adoring everybody's readings Stephanie and Patricia. So great. Fabulous. Okay. The one piece of information. Well, I don't know if I do wish I had known it. I think my innocence allowed me to keep writing. What I didn't at all understand is that there's maybe a one in 1 million chance that a poet and novelist can ever make anything approaching a decent living.

I found myself a single mother living in the Bay area. And I somehow thought after I got the, you know, the okay advance for this novel, I felt wealthy. And I thought, well, I will be fine and it's going to be like this from here on in. But then the crash of 2008 happened. And the next two book proposals I had written, which my agent and I fully expected would result in contracts, neither came through. I'd been dancing at the edge of the financial precipice and everything came crashing down for me.

So, you know, if I had known, would I have wanted to save myself, the, the anguish and the anxiety of really not knowing, I mean, I had a son who was, you know, a teenager and I was wanting to put him through college and so forth. And it was, you know, you don't do that on whatever a poet and novelist earns, which is, you know, next to nothing, really.

If you have to divide those advances out into the days in which you work, you know, you're maybe making 10 cents a day or something. I don't know. I've never really figured it out. Some people are able to do it with your bestsellers, but really, I don't know the exact statistic. I think the Authors Guild probably is in possession of this, but I don't think it's much better than one in a million. It's really hard.

So my piece of advice is make sure that at least one adult member of your household has a salary and health insurance and, you know, even better, a pension because you'd better just be willing to write for the love of writing. There are, most likely, absolutely no financial rewards involved. You know, if you want financial rewards get a different profession, but the emotional rewards of writing for me have, they've not only been enormous, they've been absolutely salvational. They have kept me alive and full of joy at being alive.

Carol Cram:

Oh, that's wonderful advice. I'm glad you actually touched on the, the making a living because actually nobody's really touched on that and it, you know, it really is important to acknowledge that we really do have to do this for love because even if your first novel is the bestseller, that doesn't mean your next one will be, or you'll even get it published. We all know what that feels like, but yes, you have to do it for the love and it is challenging, for sure.

Thank you for sharing that with us, Barbara, that's good advice. And Stephanie.

Stephanie Cowell:

I would heartily second what Barbara said, I for me, I sorta said, well, when I'm really a novelist, you know, then I will make a living and of course this isn't true for probably 99.99% of us. There's a little dark spot in my heart, you know? And despite my books being translated, and in libraries and written about, I kept thinking oh golly, it's not what I'm supposed to do, but it's really, as Barbara said, it's been a wonderful life.

I mean, this is wonderful. I have met people I've met, go where I've gone. It's been, it's just been so many extraordinary things happened. I would also say that, yes. ask people for advice. If you want to give your book out to others to read, you should. I mean, if you look in the acknowledgements of almost any published novel, you will find thank you for my first readers, my second readers, my third readers, you know, my husband, my agent, and this huge list of people.

If people say something and it doesn't ring very true to what you want to do, remember it is your novel in the end, because everybody will have different opinions. And if someone says something and it doesn't ring completely true to you, wait to hear from two or three or four other people. If they all start saying the same thing, you might want to just pay a little attention to it. But yeah, I think that's an important thing to remember as you, as you go out there.

Carol Cram:

Good advice. Exactly. Yes. I mean, I think you have to believe in your book yourself, but you know, if four or five people are all saying the same thing, then you do want to listen. I actually just had that experience with the novel that's just coming out. A few people, more than a few people, noticed something about it that really wasn't ringing true. And so I changed it. Luckily I had time, but you know, it's okay to listen to your readers, not over overly, but it's kind of a balance, isn't it? Thank you, Stephanie.

And so Patricia, what advice did you wish you'd known or any advice that you'd like to share?

Patricia Morrisroe:

Well, I came at writing novels, a historical novel, uh, very late in my career. And I'm glad it happened that way, I think, because it's much more challenging now across the board for nonfiction and fiction writers. It just is.

So I agree with both Barbara and Stephanie, that finances are just not the way, uh, they were, even for me, 20, 30 years ago, there were magazines where you could write and make a decent living which I did at New York Magazine for most of the 80s. So people I knew who were writing novels could also write and had day jobs as writers. That really is not possible now. I mean, for the, for the lucky few, it may be, but you really have to teach because you cannot make a living this way.

What surprised me, and I was lucky because I didn't have to go through this, but I didn't realize that before you submitted a novel, you had to complete it. As a non-fiction writer, you're usually selling a proposal that may be 35 to you know, 40 pages. So that's a lot different. You may be doing a lot of research in order to get to that 35 to 40 pages, but it is not the years that you might take to write a historical novel.

So, I mean, I applaud people who would sit down for so long with the question mark of, am I going to sell it? I mean, that takes such enormous fortitude. So I think for somebody contemplating that, there should be nothing else you really want to do other than write a novel because it's very, it's increasingly tough to get published. Advances are really not what they were, although surprisingly more and more people want to become writers. So I think it's, yeah, have a plan because I know growing up and living in New York, friends who are writers and friends who are successful writers and honestly, very few of them make a living.

I mean, and you'd be very surprised, very few of them do. Do you know, the key is to get a decent enough advance. Do I know many people who've actually earned out their royalties? Very, very few. So it's exceptionally tough.

I knew that because as I said, I came to writing historical fiction quite late, and it's not the reviews. You're not waiting for the reviews because all the review outlets, like The New York Times, The Washington Post used to have the Washington Post Book, you know, Book World. So there are far fewer places to be reviewed. Yeah, you can be reviewed on blogs, but the major review outlets are much more selective and they're just not reviewing the way they used to. And you don't know if a reviewer's going to pan or love your book and I've been in both situations. So you can't be looking forward to the reviews. You can't be looking forward to the money. For me, it's always been the process of writing, the process of learning and the process of writing, which I love. And if anything happens down the line, that's wonderful, but I don't really expect it.

Carol Cram:

Yes, I'm learning this more and more. I'm now on my fourth novel and yes, it's the process. You have to love the process because the money, who knows what's going to happen. I was fortunate. I wrote textbooks for decades and, but they do sell. So that was great. But I tell you, I wouldn't have been able to do this without that career.

Thank you so much, Patricia and Barbara and Stephanie, this has just been so much fun. Because we have so many different or three different points of view coming through, but also I'm enjoying hearing all the commonalities between us as authors, especially authors of historical fiction.

So I'm going to say thank you very much for being on the Art In Fiction Podcast.

Barbara Quick:

Thank you, Carol. My pleasure.

Carol Cram:

Yes. And I have to jump in here and also thank Barbara in particular because it was her idea to bring the three of you together. And I really appreciate it.

Stephanie Cowell:

Thank you all, all three of you, very much.

Patricia Morrisroe:

Thank you to my friends, Stephanie and Barbara. And I think writing is such a lonely process. It's always wonderful when you get together with other writers, because you share so much, you just, with another writer, you get one another, there is that commonality of writing that brings people together, uh, which I, I really appreciate it. So again, thank you all.

Carol Cram:

Exactly right. I think that is why I'm having such a great time is we get each other, we know what it's like to sit in front of a blank screen. We know what it's like when things don't go right and those dark nights of the soul. But we also know what it's like when it's fabulous.

I’ve been speaking with Barbara Quick, Stephanie Cowell, and Patricia Morrisroe, all authors of novels listed in the Music category on Art In Fiction at www.artinfiction.com. Links to their novels and websites can be found in the show notes, along with the link to an extended free trial of SmarterQueue, the social media management tool I use every day.

Don’t forget to follow Art In Fiction on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/fictionandart/, and please give The Art In Fiction Podcast a positive review wherever you get your podcasts.

Thanks so much for listening!